Your GM picked out the adventure, did all of the background work, fleshed out the NPCs, balanced treasure and other rewards. Now it’s finally time to run the adventure, it’s up to the GM to find a way to motivate your character. Right?

Your GM picked out the adventure, did all of the background work, fleshed out the NPCs, balanced treasure and other rewards. Now it’s finally time to run the adventure, it’s up to the GM to find a way to motivate your character. Right?

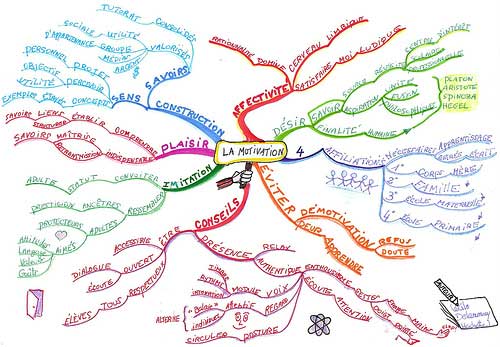

[Photo from http://www.flickr.com/photos/philippeboukobza/ / CC BY 2.0]

Wrong.

True, the GM will most likely provide you a motivation for going on the adventure, but you can help by providing your own motivation for your character.

While “My character wouldn’t do that” can be a legitimate concern (I’m a “method actor”-style player, myself), it’s not helpful. If you try hard enough, there’s usually some way you can provide your character with a motivation to undertake the adventure.

Character History

Even if you don’t have a detailed backstory for your character, you can find a way to work something about this adventure into your character’s history. In fact, it’s probably easier to do it without a detailed history. But even if you’ve written down information for every month of your character’s life, you can still usually find a way to work a motivation for the adventure in there.

Perhaps you stumbled across this dungeon when you were growing up and always wondered what was down there that was so dangerous your parents wouldn’t let you explore it. Or your now-deceased mother had been an adventurer but had fled from this dungeon before exploring it thoroughly and you want to find out what could make a generally fearless woman flee in terror.

These are simply suggestions; you’ll do much better to find some reason yourself. The point is, that it doesn’t have to be a driving passion to provide motivation. Simple curiosity can be enough. Maybe the owner owes you some money and if you can’t get the money, you’re going to take payment in goods of equal value. Or perhaps you want to prove yourself a better adventurer than your mother who’s shadow you’ve been in since you started your career.

Character Relationships

That brings us to our next type of motivation: other people and the relationships your character has with them. It could be your favorite uncle asked you to check out the city sewers to find proof of the giant cybernetic rats and cockroaches he’s always said live down there. Maybe your familiar or a favorite pet wandered into the Mayor’s Mansion and hasn’t been seen or heard from since. Or maybe, just maybe, your brother dared you to go into the spooky cave.

Again, the reasons don’t have to be deep of life-changing or part of The Big Picture. It can be petty concerns. The important thing is to have a reason that will motivate you to undertake the adventure. It could even be something simply as the party’s cleric said “Please” when he asked you to come along. Of course, if you want to have this adventure affect your character deeply, go for it.

Character Goals

This brings us to our last set of motivations: your character’s goals. Maybe you want to collect one of every type of potion in the world. Or maybe you need some scrapings from the wall to to mix the exact shade of grey paint to finish your current project. See, even here you don’t need grandiose ideas — simple ones will do as long as it gets your character moving.

Of course, you’ll want to clear your motivation with your GM. If he hears, for instance, that you think there may be potions for your collection, then he’ll most likely go out of his way to put one in there as a reward. Maybe you just want to complete your rock collection and the last type of rock you need is said to exist in this lich-controlled forest. placed in there.

Brainstorming or “Mind-Mapping” can help you find a reason. You can get special software for that, but I find good ol’ pen and paper work great for the job. If you’re really stuck, you might try having the GM other person you trust over for a brainstorming party. If something doesn’t come to you immediately, keep trying until you come up with something you can play. You’ll find the game much more enjoyable.

Other Player Month Posts:

Articles Zemanta thinks might be related

- The Characterisation Puzzle: When personalities are hard to find (campaignmastery.com)

- The DM Treasure Chest (dungeonmastering.com)

- Beyond the Module (dungeonmastering.com)

- The Characterisation Puzzle: The Inversion Principle (campaignmastery.com)

- Six Self Motivation Tips To Give Yourself A Boost! (slideshare.net)

- 10 Ways To Find New Motivation (psychcentral.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=a9c48f1d-d82d-420c-9b2b-01fcf956e82a)

Here it is–the first post of our “Player Month”, designed to give advice to the players on how to make a game better. After all, the GM isn’t the only one playing and the players share some responsibility for making a game great.

Here it is–the first post of our “Player Month”, designed to give advice to the players on how to make a game better. After all, the GM isn’t the only one playing and the players share some responsibility for making a game great.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=8d745098-b25d-4d91-a243-512341943814)

Whether as a PCs or an NPCs, evil characters tend to get the short end of the stick. All too often, they’re portrayed as short-sighted, reactionary, shallow, and … well, stupid. Frequently, all evil characters look and act the same, like they are clones of one another. Which is a real shame; after all, what’s more engaging to your players than defeating a worthy opponent? Here are eight tips for making your evil characters more in-depth and engaging.

Whether as a PCs or an NPCs, evil characters tend to get the short end of the stick. All too often, they’re portrayed as short-sighted, reactionary, shallow, and … well, stupid. Frequently, all evil characters look and act the same, like they are clones of one another. Which is a real shame; after all, what’s more engaging to your players than defeating a worthy opponent? Here are eight tips for making your evil characters more in-depth and engaging.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=08bed60d-ccd2-4f61-ab6f-a836b8dfb517)

We all get them: the incessant rules lawyer who challenges your every call; the “loopholer” who will exploit everything not nailed down in the rules to gain that extra +1 advantage; the player who takes everything that happens to their character as an attack on themselves…

We all get them: the incessant rules lawyer who challenges your every call; the “loopholer” who will exploit everything not nailed down in the rules to gain that extra +1 advantage; the player who takes everything that happens to their character as an attack on themselves…