Here it is — the final post of our What’s in a Name? series. Today we’re talking about alphabets.

Well, actually not about alphabets. While you can create a whole new alphabet for your language, it’s a lot of work to do just to create names. Especially since unless you’re writing out all of your game materials by hand, you’ve got to create either a true font or a set of dingbats to represent your new alphabet.

Well, actually not about alphabets. While you can create a whole new alphabet for your language, it’s a lot of work to do just to create names. Especially since unless you’re writing out all of your game materials by hand, you’ve got to create either a true font or a set of dingbats to represent your new alphabet.

You can actually create something unique by using Roman letters. After all, most languages in Europe and the Americas all use some variation of Roman letters and they all manage to look different.

(Photo courtesy of: http://www.flickr.com/photos/fdecomite/ / CC BY 2.0)

Go Back to Your Sounds

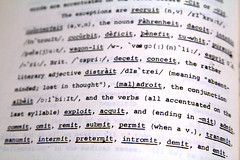

Remember the list of sounds we made back on the Day 2? It’s time to pull that out. What you want to do is assign one letter or letter combination to every sound you have. What you’re creating here is actually called an orthography.

Now, you can mix up the letters and sounds — but I wouldn’t recommend it. What I mean by that is, you can assign the “sh” sound to the letter “a”. I wouldn’t recommend it because it’ll be a constant headache for you and your players. You’ll constantly have to look back and forth between your names and your “alphabet” and I’d be very surprised if your players didn’t revolt by the second game session as they try to remember that “Shewsberry” is actually pronounced “thantcamms”.

What you do want to do though, is settle on one way of writing each phoneme you have. Even though in English (for example) “c” can make an “s” or a “k” sound and more than one letter in the alphabet can make the same sound, for simplicity’s sake, I’d recommend one sound, one letter combinations. That way, you know that “Cebunclane” is always pronounced “ke-bunk-la-ne” and not “see-boon-clain”.

A Note About Diacritics

One obvious way to make your language look different is by using a lot of diacritics. But this can also create a huge headache as you have to remember how to type them or pause frequently while writing to use the “insert special character” (or equivalent) function of your computer. And if you ever want to post your names online, keep in mind that HTML has a very limited set of special characters it supports.

You can actually get a very different look to your names just by using combinations of letters not normally found in English and peppered with a few very common diacritics. Here’s some examples:

- Nord-Pas-de-Calais (French)

- Lübeck (German)

- Zaragoza (Spanish)

- Algyógy (Hungarian)

- Bizusa-Bâi (Romanian)

Have fun with this. It can be some work, initially, but once you’ve created it, it really does help give your world a unique flavor. Then, if you decide you do want to create a full language for your world at a later date, you’ve already laid some of the foundation work.

This article series was inspired by Mark Rosenfelder’s Language Construction Kit and I’ve drawn on it heavily as a resource. If you’re interested in a creating a language of your own, his site is a great place to start.

Other Posts in This Series

Related articles by Zemanta

- Alphabet Juice (litmob.com)

- GCSE league tables: languages in decline (telegraph.co.uk)

- It’s all Greek to me (barbgibson.x.iabc.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=cd662975-45ae-4b8b-a18f-1447e52a2635)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=5c86ab2e-8010-4153-b0e5-62ea51e8ce82)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=422e1afc-6f4f-4be6-b869-fcf7d906d052)